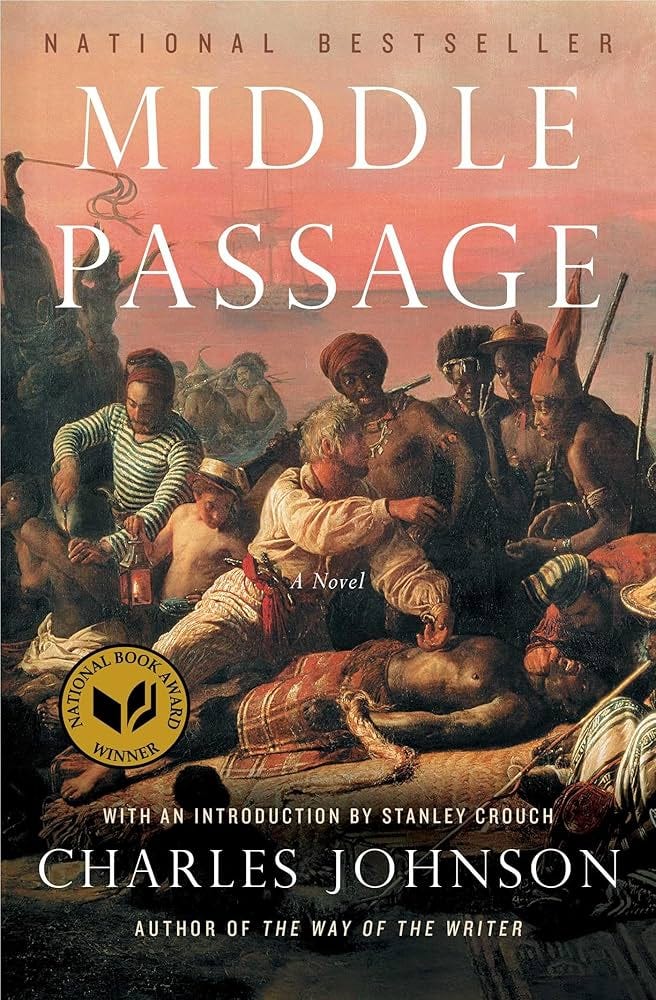

Review: "Middle Passage" by Charles R. Johnson

National Book Award Winner: 1990

Publication Year: 1990

Category: Fiction

“Brother, my people have a saying: Wish in one hand, piss in the other, and see which hand fills up first. But if this could be, we would set sail to Africa. All that has happened in the last few weeks would be as a dream, a tale to thrill—and terrify—our grandchildren.”

This is the inaugural review post for what you might call a fresh new journal on American literature. In covering the National Book Awards (NBAs), it at first sounded logical for me to read something from the first year of the revived Awards, that being 1950. There were only three categories that year: Fiction: Nonfiction, and Poetry. But for better or worse I’m a mood-based reader, and while I had it in my mind to read Nelson Algren’s The Man with the Golden Arm, the first NBA Fiction winner, Charles R. Johnson’s Middle Passage sounded more appetizing to me in the moment. I had picked up a copy pretty much on a whim not too long ago, and luckily for me (and you) this book is still in print and in bookstores. Incidentally this is a novel written as a series of journal entries, being the narrative of Rutherford Calhoun, recounting a very strange and eventful sea journey in 1830.

Johnson is a writer of fiction and nonfiction, a screenwriter for TV, a cartoonist, and a retired college professor. He was born in 1948, in Illinois, but has spent much of his life in Seattle, Washington. Middle Passage was his third novel and fourth fiction book, following the short-story collection The Sorcerer’s Apprentice. He was the first black American author to win the NBA for Fiction in nearly 40 years, after Ralph Ellison’s landmark 1952 novel Invisible Man. Johnson’s work as a whole remains pretty obscure and undervalued, with Middle Passage being easily his most-read book according to Goodreads; and even then, it’s not as popular as it should be. Fans of Herman Melville (I admit I’m one of those) and sea stories in general would do well to seek out this short but densely packed novel. It’s a thoroughly “literary” pastiche of 19th century conventions while still being entertaining. Hell, if you’re worried about it being as challenging as Moby-Dick, don’t be.

As to the plot, the gist is that Rutherford Calhoun is a former slave, raised in Illinois alongside his brother Jackson, their master being the benevolent and guilt-ridden Reverand Chandler. Having inherited slaves from his father, Chandler eventually decided to give the Calhoun brothers their freedom, with Jackson becoming a very pious “gentleman of color” while Rutherford took on a life of petty crime. Despite being educated and eloquent, especially by the standards of his time, Rutherford makes a living in the New Orleans underworld at the novel’s beginning, resenting his brother for what he sees as having sold out to whites. Rutherford is, if nothing else, his own man, which leads to the problem of being blackmailed into marrying the homely but willing black schoolteacher Isadora Bailey. Isadora really does love Rutherford; but while Rutherford likes her well enough, the thought of a shotgun wedding to appease his hungry creditors strikes him as a raw deal. Marriage (so Rutherford thinks) is not in the cards.

To sea it is, then!

Of course, had Rutherford known in advance about what his voyage aboard the illicit slave ship Republic would be like, he would’ve readily taken the marriage deal. Now, it’s understandably tempting (and I do believe Johnson encourages this) to compare and contrast Middle Passage with Moby-Dick, a comparison that starts from the very beginning. Ishmael and Rutherford are both nomads who think rather dimly of the ruling class, never mind that their antics would be happening only a decade or two apart. But whereas Ishmael takes to see because of a bout of melancholy, Rutherford’s reasons are more dramatic. In keeping with its protagonist’s proactive attitude, Middle Passage is more plot-driven (indeed more conventionally structured) than Moby-Dick, which is not a bad thing. While the influence is apparent, and there’s even an overlap in subject matter, Johnson’s novel more explicitly deals with the issues of chattel slavery and white supremacy (including black self-loathing under these conditions) that would soon tear the US apart. Melville loathed slavery, but he was also writing circa 1850, as a left-leaning white man in the northeast, while Johnson strikes similar ground from quite a different angle.

Rutherford knocks a drunken sailor by the name of Josiah Squibb unconscious and takes his papers, boarding the Republic as a seaman. This ruse works about as well as the average SpaceX rocket, though, which is to say it doesn’t. One nap later and the crew outs Rutherford as a stowaway, with Squibb still having made it aboard. The good news is that my man gets to stay on the ship, given that the Republic’s crew is largely made up of lunatics, haters, and punk trash anyway. The ship is also quite literally falling apart, its days being numbered by the time we get there, which may or may not be a metaphor for how, by 1830, the seeds for the Civil War had already been sown. Most of the crewmen are lowlifes, the big exception being Peter Cringle, the first mate and Rutherford’s first friend. Cringle comes from a bourgeois background and serves as the local voice of reason.

And then there’s Captain Falcon.

No, not that one.

Falcon is a real piece of work. He’s a pederast, having sexual relations with Tommy, the cabin boy who’s somewhere in his teens. He also casually mentions in having indulged in cannibalism, that thing which befalls some unfortunate crews. Despite being either a dwarf or short enough to be confused for someone with that condition, Falcon looms tall over the ship and its crew. Falcon is aware that he’s captain of a doomed ship, and he borders on being aware that he’s just a character in a novel. Officially the Republic is supposed to take back some slaves of the Allmuseri tribe (as far as I can tell being of Johnson’s invention), sold by an amoral Arab merchant; but for Falcon the real prize is an Allmuseri artifact, kept in a crate and apparently with the ability to turn those who gaze upon it insane.

Several of the characters in Middle Passage, namely the white folks aboard the Republic, correspond with shipmates in Moby-Dick. Squibb is meant to be Stubb, Cringle is clearly Starbuck, Falcon is Ahab, and Tommy is the black cabin boy Pip. You may recall that Pip is driven mad by a near-death experience in the ocean deep, and similarly Tommy loses his mind upon seeing what’s inside that special crate. You may also recall that Ishmael becomes fast friends with a Polynesian prince named Queequeg, who comes from a fictitious Pacific tribe. In Middle Passage, Queequeg is split into two people, those being the highly intelligent man Ngonyama and the young girl Baleka, both on the ship as Allmuseri slaves. Rutherford becomes friends with Ngonyama while coming to see Baleka as like a surrogate daughter. It helps that Rutherford is the only black shipmate, although this ends up being a double-edged sword for his relationships with others.

Rutherford’s arc, compared to that of his Moby-Dick counterpart, is easy enough to discern. There are, after all, large stretches of Moby-Dick where Ishmael seems to evaporate as a character, whereas Rutherford is always figuratively in the driver’s seat. He starts as a rogue who only really thinks of himself, but his interactions with members of the Allmuseri tribe give him perspective on the tangled relations between whites, black Americans, and native Africans. The Allmuseri see the whites as “Raw Barbarians,” whereas Rutherford is a “Cooked Barbarian.” Not among the whites, and yet still an outsider to the Allmuseri. It’s a harsh and protracted lesson in solidarity between a freed slave and those who are sold into slavery. Even at just 23 years old, the life of having been born and raised a slave made a bitter man out of Rutherford and aged him beyond his years. This, combined with Chandler giving him a generous education, can explain his rather verbose recounting of his tale. I found it a bit distracting at first, but eventually I did come to see a logic behind it, never mind that Rutherford is writing these entries after the fact.

Despite being just over 200 pages, Middle Passage is more ambitious than it looks; and yet it’s still an adventure novel, being a proud member of a long line of sea stories, from The Odyssey through the novels of Herman Melville and Joseph Conrad. I’m a sucker for the premise of ship-as-society, or rather the ship as a microcosm for society, and Johnson takes good advantage of it. While it pays homage to Melville (and I suspect also Conrad, more implicitly), Johnson gives the premise a modern and decidedly black-left sensibility that a reader in [the current year] might find more appealing, or at least less intimidating. It also helps that while paragraphs often run for whole pages at a time (lacking a typewriter, it makes sense that Rutherford would write his journal in longhand), there’s a constant web of intrigue that should keep the reader occupied. This is a good one.